Exhibition information

Peter Wegner

THE ERROR WAS REPEATED

THE ERROR WAS REPEATED

2. Februar bis 23. Juni 2018

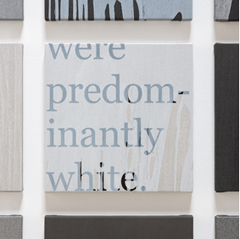

For the last 25 years, artist Peter Wegner has focused on color. His new body of work, COLOR CORRECTIONS, draws on references to color published in The New York Times. In a section known as “Corrections,” the newspaper acknowledges its previous errors and attempts to set the record straight. Wegner prints fragments of these corrections onto canvas. Over this, he pours thin veils of paint ranging from coal black to translucent white to silvery gray.

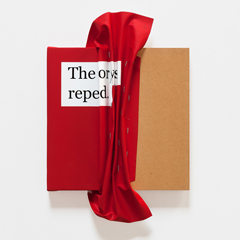

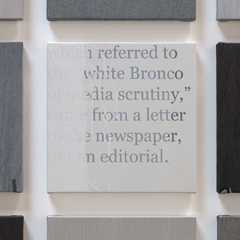

WHITE BRONCO, the title of this work, refers to the color and model of car used by O.J. Simpson to evade police on live camera in 1994. Other references include the White House; all-white membership in a country club; the “black king” of a chess game; and Invisible Man, the 1952 novel by African-American writer Ralph Ellison.

Wegner thus invokes the overlapping worlds of literature, politics, history, and mass media. His work provides a new frame of reference. It’s one in which we are all implicated in an ongoing dialogue about black and white, right and wrong, and the many shades of gray in between.

artist statement

CORRECTION

Everybody makes mistakes. Then what?

Institutions and individuals all face the same choice: Pretend it didn’t happen, or acknowledge it and make it right. For a newspaper, printing a correction notice is an article of faith. It establishes a baseline of credibility, affirming the value of reliable reportage.

The language of a correction notice is rigid and decorous, therefore often funny. In their efforts to address even small errors of fact, editors might seem to miss the larger point. But that’s exactly the point: scale doesn’t matter. All errors are, in fact, the same size; all require correction. So even when the issue appears to be minor, it’s no small matter. Much depends on this kind of accountability. Relationships of all kinds, political as well as personal. Democracy, for example.

The text in this body of work is drawn from The New York Times. I’ve been reading it for almost 40 years, and that’s how far back my research extends. When I started subscribing to The Times as a university student in 1981, it was fashionable to go first to “Obituaries.” I’ve always gone first to “Corrections.” Both sections are memorials. The obituary memorializes a life well lived; a correction memorializes a fact that failed. Together, these two departments tell us all the news we know for sure: sooner or later we’re going to die, but before we do, we’re going to get a bunch of things wrong.

A correction notice is a mea culpa just a few sentences long, therefore abstract in various ways. It points in the wrong direction, backwards. There it locates an error you might not have noticed in an article you probably didn’t read. I heighten that ambiguity by taking just a sentence or two, obscuring the original reference.

It’s not uncommon for a mistake to be printed more than once before it’s caught. In a few cases, the mistake has been repeated dozens of times across decades. The Times defaults to the same phrase every time: The error was repeated. This, one might say, is the human condition – to make the same mistake twice. It’s a problem built into being alive.

The years go by and the errors accumulate. It’s been widely observed that the notion of truth itself is under attack. Sometimes the best defense is to glance over your shoulder, along with The Times, and try to figure out what the hell just happened, where we went wrong, and how to set the record straight.

Peter Wegner

Berkeley CA

January 2018

For the last 25 years, artist Peter Wegner has focused on color. His new body of work, COLOR CORRECTIONS, draws on references to color published in The New York Times. In a section known as “Corrections,” the newspaper acknowledges its previous errors and attempts to set the record straight. Wegner prints fragments of these corrections onto canvas. Over this, he pours thin veils of paint ranging from coal black to translucent white to silvery gray.

WHITE BRONCO, the title of this work, refers to the color and model of car used by O.J. Simpson to evade police on live camera in 1994. Other references include the White House; all-white membership in a country club; the “black king” of a chess game; and Invisible Man, the 1952 novel by African-American writer Ralph Ellison.

Wegner thus invokes the overlapping worlds of literature, politics, history, and mass media. His work provides a new frame of reference. It’s one in which we are all implicated in an ongoing dialogue about black and white, right and wrong, and the many shades of gray in between.

artist statement

CORRECTION

Everybody makes mistakes. Then what?

Institutions and individuals all face the same choice: Pretend it didn’t happen, or acknowledge it and make it right. For a newspaper, printing a correction notice is an article of faith. It establishes a baseline of credibility, affirming the value of reliable reportage.

The language of a correction notice is rigid and decorous, therefore often funny. In their efforts to address even small errors of fact, editors might seem to miss the larger point. But that’s exactly the point: scale doesn’t matter. All errors are, in fact, the same size; all require correction. So even when the issue appears to be minor, it’s no small matter. Much depends on this kind of accountability. Relationships of all kinds, political as well as personal. Democracy, for example.

The text in this body of work is drawn from The New York Times. I’ve been reading it for almost 40 years, and that’s how far back my research extends. When I started subscribing to The Times as a university student in 1981, it was fashionable to go first to “Obituaries.” I’ve always gone first to “Corrections.” Both sections are memorials. The obituary memorializes a life well lived; a correction memorializes a fact that failed. Together, these two departments tell us all the news we know for sure: sooner or later we’re going to die, but before we do, we’re going to get a bunch of things wrong.

A correction notice is a mea culpa just a few sentences long, therefore abstract in various ways. It points in the wrong direction, backwards. There it locates an error you might not have noticed in an article you probably didn’t read. I heighten that ambiguity by taking just a sentence or two, obscuring the original reference.

It’s not uncommon for a mistake to be printed more than once before it’s caught. In a few cases, the mistake has been repeated dozens of times across decades. The Times defaults to the same phrase every time: The error was repeated. This, one might say, is the human condition – to make the same mistake twice. It’s a problem built into being alive.

The years go by and the errors accumulate. It’s been widely observed that the notion of truth itself is under attack. Sometimes the best defense is to glance over your shoulder, along with The Times, and try to figure out what the hell just happened, where we went wrong, and how to set the record straight.

Peter Wegner

Berkeley CA

January 2018

DOUBLE ERROR WITH FLAPS UP/DOWN, 2017 (Detail)

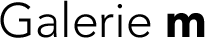

SCRUNCHED AND STAPLED, 2017

CRUMPLED AND STAPLED, 2017

WHITE BRONCO, 2017 (Detail)

WHITE BRONCO, 2017 (Detail)

WHITE BRONCO, 2017 (Detail)